Hi georgios,some findings on Flavius Josephus

start content

A Roman portrait bust said to be of Josephus

Josephus (37 – sometime after 100 AD),[1] who became known, in his capacity as a Roman citizen, as Titus Flavius Josephus,[2] was a 1st-century Jewish historian and apologist of priestly and royal ancestry who survived and recorded the Destruction of Jerusalem in 70. His works give an important insight into first-century Judaism.

Life

Josephus, who introduced himself in Greek as "Iosepos (Ιώσηπος), son of Matthias, an ethnic Hebrew, a priest from Jerusalem",[3] fought the Romans in the First Jewish-Roman War of 66-73 as a Jewish military leader in Galilee. After the Jewish garrison of Yodfat was taken under siege, the Romans invaded, killing thousands, and the remaining survivors who had managed to elude the forces committed suicide. However, in circumstances that are somewhat unclear, Josephus and one of his soldiers surrendered to the Roman forces invading Galilee in July 67. He became a prisoner and provided the Romans with intelligence on the ongoing revolt. The Roman forces were led by Flavius Vespasian and his son Titus, both subsequently Roman emperors. In 69, Josephus was released (cf. War IV.622-629) and according to Josephus's own account, he appears to have played some role as a negotiator with the defenders in the Siege of Jerusalem in 70.

In 71, he arrived in Rome in the entourage of Titus, becoming a Roman citizen and Flavian dynasty client (hence he is often referred to as Flavius Josephus - see below). In addition to Roman citizenship he was granted accommodation in conquered Judea, and a decent, if not extravagant, pension. It was while in Rome, and under Flavian patronage, that Josephus wrote all of his known works.

Although he only ever calls himself "Josephus", he appears to have taken the Roman nomen Flavius and praenomen Titus from his patrons.[4] This was standard for new citizens.

Josephus's first wife perished together with his parents in Jerusalem during the siege and Vespasian arranged for him to marry a Jewish woman who had been captured by the Romans. This woman left Josephus, and around 70, he married a Jewish woman from Alexandria by whom he had three male children. Only one, Flavius Hyrcanus, survived childhood. Josephus later divorced his third wife and around 75, married his fourth wife, a Jewish girl from Crete, from a distinguished family. This last marriage produced two sons, Flavius Justus and Simonides Agrippa.

Josephus's life is beset with ambiguity. For his critics, he never satisfactorily explained his actions during the Jewish war — why he failed to commit suicide in Galilee in 67 with some of his compatriots, and why, after his capture, he cooperated with the Roman invaders. Historian E. Mary Smallwood wrote:

(Josephus) was conceited, not only about his own learning but also about the opinions held of him as commander both by the Galileans and by the Romans; he was guilty of shocking duplicity at Jotapata, saving himself by sacrifice of his companions; he was too naive to see how he stood condemned out of his own mouth for his conduct, and yet no words were too harsh when he was blackening his opponents; and after landing, however involuntarily, in the Roman camp, he turned his captivity to his own advantage, and benefitted for the rest of his days from his change of side.[5]

However, his critics ignore the fact that Simon Bar Giora and John of Giscala, both extreme zealots and great opponents of Josephus, who stayed in Jerusalem and led the war against Rome in its final stage, in a moment of truth, preferred life over suicide and humbly surrendered to the Romans. At any rate, those who have viewed Josephus as a traitor and informer have questioned his credibility as a historian — dismissing his works as Roman propaganda or as a personal apologetic, aimed at rehabilitating his reputation in history. More recently, commentators have reassessed previously-held views of Josephus. As P.J. O'Rourke quipped,

Reason dictates we should hate this man. But it's hard to get angry at Josephus. What, after all, did he do? A few soldiers were tricked into suicide. Some demoralizing claptrap was shouted at a beleaguered army. A wife was distressed... all of which pale by comparison to what the good men did. For it was the loyal, the idealistic and the brave who did the real damage. The devout and patriotic leaders of Jerusalem sacrificed tens of thousands of lives to the cause of freedom. Vespasian and Titus sacrificed tens of thousands of more to the cause of civil order. Even Agrippa II, the Roman client king of Judea who did all he could to prevent the war, ended by supervising the destruction of half a dozen of his cities and the sale of their inhabitants into slavery. How much better for everyone if all the principal figures of the region had been slithering filth like Josephus.[6]

Josephus was unquestionably an important apologist in the Roman world for the Jewish people and culture, particularly at a time of conflict and tension. He always remained, in his own eyes, a loyal and law-observant Jew. He went out of his way both to commend Judaism to educated Gentiles, and to insist on its compatibility with cultured Graeco-Roman thought. He constantly contended for the antiquity of Jewish culture, presenting its people as civilised, devout and philosophical.

Eusebius reports that a statue of Josephus was erected in Rome.[7]

[edit] Significance to scholarship

The works of Josephus provide crucial information about the First Jewish-Roman War and are also important literary source material for understanding the context of the Dead Sea Scrolls and post-Second Temple Judaism. Josephan scholarship in the 19th and early 20th century became focused on Josephus' relationship to the sect of the Pharisees. He was consistently portrayed as a member of the sect, but nevertheless viewed as a villainous traitor to his own nation - a view which became known as the classical concept of Josephus. In the mid 20th century, this view was challenged by a new generation of scholars who formulated the modern concept of Josephus, still considering him a Pharisee but restoring his reputation in part as patriot and a historian of some standing. Recent scholarship since 1990 has sought to move scholarly perceptions forward by demonstrating that Josephus was not a Pharisee but an orthodox Aristocrat-Priest who became part of the Temple establishment as a matter of deference and not willing association (Cf. Steve Mason, Todd Beall, and Ernst Gerlach).

Josephus offers information about individuals, groups, customs and geographical places. His writings provide a significant, extra-biblical account of the post-exilic period of the Maccabees, the Hasmonean dynasty and the rise of Herod the Great. He makes references to the Sadducees, Jewish High Priests of the time, Pharisees and Essenes, the Herodian Temple, Quirinius' census and the Zealots, and to such figures as Pontius Pilate, Herod the Great, Agrippa I and Agrippa II, John the Baptist, James the brother of Jesus, and a disputed reference to Jesus. He is an important source for studies of immediate post-Temple Judaism (and, thus, the context of early Christianity).

A careful reading of Josephus' writings allowed Ehud Netzer, an archaeologist from Hebrew University, to confirm the location of Herod's Tomb after a fruitless search of 35 years - on top of tunnels and water pools at a flattened desert site, halfway up the hill to the Herodium, 12 kilometers south of Jerusalem - exactly where it should be according to Josephus writings.

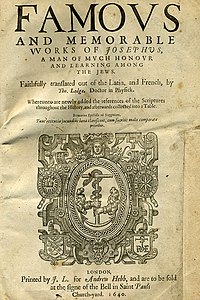

For many years, the works of Josephus were printed only in an imperfect Latin translation from the original Greek. It was only in 1544 that a version of the Greek text was made available, edited by the Dutch humanist Arnoldus Arlenius. The first English translation appeared in 1602 by Thomas Lodge with subsequent editions appearing throught the 17th century. However, the 1544 Greek translation formed the basis of the 1732 English translation by William Whiston which achieved enormous popularity in the English speaking world and which is currently available online for free download by Project Gutenberg. Later editions of the Greek text include that of Benedikt Niese, who made a detailed examination of all the available manuscripts, mainly from France and Spain. This was the version used by H. St J. Thackeray for the Loeb Classical Library edition widely used today.

A 1640 edition of the works of Josephus translated by Thomas Lodge which originally appeared in 1602.

Works

A fanciful representation of Flavius Josephus, in an engraving in

William Whiston's translation of his works

- (c. 75) War of the Jews, or Jewish War, or Jewish Wars, or History of the Jewish War (commonly abbreviated JW, BJ or War)

- (date unknown) Josephus's Discourse to the Greeks concerning Hades (spurious; adaptation of "Against Plato, on the Cause of the Universe" by Hippolytus of Rome)

- (c. 94) Antiquities of the Jews, or Jewish Antiquities, or Antiquities of the Jews/Jewish Archeology (frequently abbreviated AJ, AotJ or Ant. or Antiq.)

- (c. 97) Flavius Josephus Against Apion, or Against Apion, or Contra Apionem, or Against the Greeks, on the antiquity of the Jewish people (usually abbreviated CA)

- (c. 99) The Life of Flavius Josephus, or Autobiography of Flavius Josephus (abbreviated Life or Vita)

Read more:

http://en.wikipedia.orghttp://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flavius_Josephus