Maybe ET’s Calling, But We Have the Wrong Phone

by Jean Tate on June 21, 2010

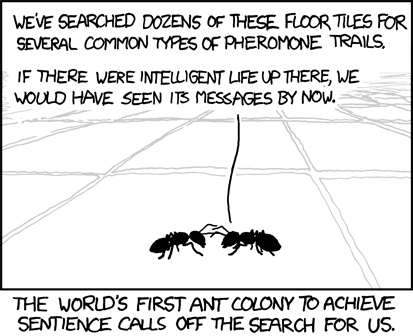

The search (xkcd)

To date, SETI (Search for ExtraTerrestrial Intelligence) has focused on ETs who ‘phone home’ using the radio part of the

electromagnetic spectrum, and even a very small region within that.

But what if ET’s phone doesn’t use radio waves? Sure the xkcd comic, is funny, but maybe it points to a deep flaw in our attempts to contact, or hear from, an ETI?

When Giuseppe Cocconi and Philip Morrison suggested the possibility of interstellar communication via electromagnetic waves in a 1959 paper in Nature, only radio was feasible, as we then had the ability to detect only artificial radio signals, if produced by ETIs with 1959 human technology. Since then we’ve developed the ability to detect a laser signal, brighter than the Sun (if only for a nanosecond) if it came from a source several light-years away … but lasers weren’t invented then.

What might ET’s equivalent of ants’ pheromones be?

Back in 1959 if you’d said that the Earth would, within a mere half century, started to go ‘radio quiet’, not many people would have taken you seriously. Yet that’s exactly what’s happened! Free to air (FTA) broadcasting, especially for TV, is being replaced by TV delivered over coaxial cable, optical fibers, or even the phone company’s twisted copper pairs. And where it’s continuing, as in satellite TV broadcasting, its power has dropped (today’s digital formats are more efficient than the old analog ones). Military radars, the brightest source of artificial radio waves by far, no longer broadcast in a single channel, but hop, rapidly, from frequency to frequency, to avoid jamming.

“Our improving technology is causing the Earth to become less visible,” says astronomer Frank Drake, SETI’s paterfamilias. “If we are the model for the universe, that is bad news.”

In the past half century SETI researchers have expanded the scope of their searches. Not only are far more radio channels being examined, but artificial signals in the optical are being sought too. How to decide which of the billions or trillions of possible radio channels to search? For example, the Allen Telescope Array will, when built, monitor a billion channels between 0.5 and 11 GHz – but that’s a trivial fraction of the entire radio waveband. Some ideas, however, seem cute; for example, the SETI Institute’s Gerald Harp has proposed searching at 4.462336275 gigahertz, in what’s called the PiHI range, because it’s the hydrogen atom’s emission frequency times pi. More seriously, Harvard University’s Paul Horowitz says optical SETI programs should really look at infrared frequencies “Stars are darker in the infrared and lasers are brighter and the smog goes away,” Horowitz says. Infrared allows astronomers to see into the galactic center, where dust scatters visible light.

There’s something rather ironic about SETI today; on the one hand, we recognize that our initial hopes were far too high, being based on overly simplistic assumptions; on the other, the tremendous progress in finding exoplanets has given us greater and greater certainty that Earth-like planets not only exist, but are, very likely, common. “All of astronomy has come to embrace this idea that there must be life out there,” says Harp.

So how to address the fact that we simply do not know what sorts of technologies a civilization like ours may have, a century or a millennium from now? After all, as Drake says “We are very conservative at SETI, we assume in our searches the existence of only things we ourselves have and know how to make.” Other scientists, and SETI enthusiasts, have proposed hunting in different electromagnetic realms, like gamma rays. Spacecraft that rely on nuclear fusion or antimatter-matter annihilation as a power source might produce such rays. But standard SETI strategy does not embrace such “speculative” scenarios.

SETI researchers, some say, should also contemplate what technologies supersmart aliens might possess and seek out the corresponding signals. In a 2008 arXiv paper, “Galactic Neutrino Communication“, John Learned of the University of Hawaii at Manoa suggested that ET could be sending beams of neutrinos Earth’s way. Energy requirements for such a beam make that scenario seem implausible, but not necessarily impossible. Detectors currently under construction, such as IceCube at the South Pole, could spot unexpected stray neutrinos. If a few with the same energy came from the same direction, astronomers would know something screwy was up.

In another paper, “The Cepheid Galactic Internet“, Learned suggests that ET could send a signal using a neutrino beam to deliver energy to a Cepheid variable. A Cepheid “blows up and comes crashing back down,” he says. “And the energy builds up and it blows again, like a geyser.” ET could leverage a Cepheid’s inherent instability by delivering a boost of energy that messes with the star‘s schedule. Looking through existing data could reveal whether such meddling has occurred. “All that is needed is people analyzing for other reasons to do their analyses in another way,” Learned says.

Drake and most others agree that SETI’s approach should be multidirectional – let a thousand alien hunters bloom. The only ideas that don’t do anybody any good, Horowitz says, are the ones for which there is no conceivable way to look. “I’d like to keep an open mind,” he says, “but not so much that my brain falls out.”

Physicist Paul Davies of Arizona State University in Tempe, however, suggests that researchers don’t need to know what to look for. Find the fishy thing first, and then argue about its origin, he says.

As Davies has argued, maybe discovering ET does indeed depend on a thought revolution. Fifty years of signal-less searching suggests that the problem could lie not with the aliens among the stars, but with ourselves.

Maybe the sentient ants should not give up, just yet.

Sources: Science News. Cocconi and Morrison’s 1959 Nature paper (copyright Nature)