Hi Amanda,

You know when I read your post my first thought was to simply write, you can disagree all you want but before you do it would be wise to research a bit of Muslim/Islamic history and then let you google away. But, being the nice guy that I am I'll give you a short history lesson via Wikipedia below and some comments of my own.

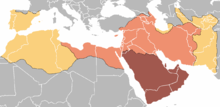

You write that the Global Elite/Illuminati "started every war since 1700 when they formed their secret society". My dear friend, the Caliphates and their quest for global domination started in 632 a few years before 1700 (so basically the Elite/Illuminati are the new kids on the block :) ). :) At that time they controlled areas in Africa, Asia and Europe. In later Caliphates they reached other parts of Europe and parts of Russia. During one period of the Caliphate Cordoba, Spain was the base for the Caliphate. All that before 1700. The last Caliphate was the Ottoman Empire which in addition to other areas also added parts of India and what is now Pakistan. Ataturk dissolved the Caliphate in 1924 and created the secular Turkish Republic. You can read more below.

So in essence what I'm saying is that the Muslims were around and controlling large parts of the world way before the secret society of the Elite/Illuminati existed. The Koran tells them that Islam will dominate the world and the Caliph will be the ruler over them all. Today is no different and they aren't shy about saying that Islam will be the one true religion in the world and they will rule it all under Shariah law.

Shalom,

Peter

The term caliphate, "dominion of a caliph ('successor')" (from the Arabic خلافة or khilāfa, Turkish: Halife), refers to the first system of government established in Islam and represented the political unity of the Muslim Ummah (community). In theory, it is an aristocratic-theocratic constitutional republic[1] (the Constitution being the Constitution of Medina), which means that the head of state, the Caliph, and other officials are representatives of the people and of Islam and must govern according to constitutional and religious law, or Sharia. In its early days, it resembled elements of direct democracy (see shura) and an elective monarchy.

It was initially led by Muhammad's disciples as a continuation of the political and religious system the prophet established, known as the 'Rashidun caliphates'. A "caliphate" is also a state which implements such a governmental system.

Sunni Islam stipulates that the head of state, the caliph, should be selected by Shura – elected by Muslims or their representatives.[2] Followers of Shia Islam believe the caliph should be an imam chosen by God from the Ahl al-Bayt (Muhammad's purified progeny). After the Rashidun period until 1924, caliphates, sometimes two at a single time, real and illusory, were ruled by dynasties. The first dynasty was the Umayyad. This was followed by the Abbasid, the Fatimid (not recognized by others outside Fatimid domain), and finally the Ottoman Dynasty.

The caliphate was "the core political concept of Sunni Islam, by the consensus of the Muslim majority in the early centuries."[3]

History

The caliph was often known as Amir al-Mu'minin (أمير المؤمنين) "Commander of the Believers". Muhammad established his capital in Medina, and after he died it remained the capital for the Rashidun period. At times in Muslim history there have been rival claimant caliphs in different parts of the Islamic world, and divisions between the Shi'a and Sunni communities.

According to Sunni Muslims, the first caliph to be called Amir al-Mu'minin was Abu Bakr Siddique, followed by Umar ibn al-Khattāb, the second of the Four Rightly Guided Caliphs. Uthman ibn Affan and Ali ibn Abi Talib also were called by the same title, while the Shi'a consider Ali to have been the first and only truly legitimate caliph.[4]

The rulers preceding these first four did not receive this title by consensus, and as it was turned into a monarchy thereafter.

After the first four caliphs, the Caliphate was claimed by dynasties such as the Umayyads, the Abbasids, and the Ottomans, and for relatively short periods by other, competing dynasties in al-Andalus, North Africa, and Egypt. Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, who received the throne after Abdulmecid II officially abolished the system of Caliphate in Islam (the Ottoman Empire) and founded the Republic of Turkey, in 1924. The Kings of Morocco still label themselves with the title Amir al-Mu'minin for the Moroccans, but lay no claim to the Caliphate.

Some Muslim countries, like Indonesia and Malaysia were never subject to the authority of a Caliphate, with the exception of Aceh, which briefly acknowledged Ottoman suzerainty.[5] Consequently these countries had their own, local, sultans or rulers who did not fully accept the authority of the Caliph.

[edit] Rashidun, 632–661

Abu Bakr, the first successor of Muhammad, nominated Umar as his successor on his deathbed, and there was consensus in the Muslim community to his choice. Umar Ibn Khattab, the second caliph, was killed by a servant. His successor, Uthman Ibn Affan, was elected by a council of electors (Majlis), but was soon perceived by some to be ruling as a "king" rather than an elected leader. Uthman was killed by members of a disaffected group. Ali then took control but was not universally accepted as caliph by the governors of Egypt, and later by some of his own guard. He faced two major rebellions and was assassinated after a tumultuous rule of only five years. This period is known as the Fitna, or the first Islamic civil war. Under the Rashidun each region (Sultanate, Wilayah, or Emirate) of the Caliphate had its own governor (Sultan, Wāli or Emir).

Muawiyah, a relative of Uthman and governor (Wali) of Syria, became one of Ali's challengers and after Ali's death managed to overcome the other claimants to the Caliphate. Muawiyah transformed the caliphate into a hereditary office, thus founding the Umayyad dynasty.

In areas which were previously under Sassanid Persian or Byzantine rule, the Caliphs lowered taxes, provided greater local autonomy (to their delegated governors), greater religious freedom for Jews, and some indigenous Christians, and brought peace to peoples demoralized and disaffected by the casualties and heavy taxation that resulted from the decades of Byzantine-Persian warfare.[6]

[edit] Umayyads, 7th–8th centuries

The Caliphate, 622–750

Expansion under the Prophet Muhammad, 622–632

Expansion during the Rashidun Caliphs, 632–661

Expansion during the Umayyad Caliphate, 661–750

Under the Umayyads, the Caliphate grew rapidly in territory. Islamic rule expanded westward across North Africa and into Hispania and eastward through Persia and ultimately to the ancient lands of Indus Valley, in modern day Pakistan. This made it one of the largest unitary states in history and one of the few states to ever extend direct rule over three continents (Africa, Europe, and Asia). Although not ruling all of the Sahara, homage was paid to the Caliph by Saharan Africa, usually via various nomad Berber tribes. However, it should be noted that, although these vast areas may have recognised the supremacy of the Caliph, de facto power was in the hands of local sultans and emirs.

For a variety of reasons, including that they were not elected via Shura and suggestions of impious behaviour, the Umayyad dynasty was not universally supported within the Muslim community. Some supported prominent early Muslims like Al-Zubayr; others felt that only members of Muhammad's clan, the Banu Hashim, or his own lineage, the descendants of Ali, should rule.

There were numerous rebellions against the Umayyads, as well as splits within the Umayyad ranks (notably, the rivalry between Yaman and Qays). Eventually, supporters of the Banu Hashim and the supporters of the lineage of Ali united to bring down the Umayyads in 750. However, the Shiʻat ʻAlī, "the Party of Ali", were again disappointed when the Abbasid dynasty took power, as the Abbasids were descended from Muhammad's uncle, `Abbas ibn `Abd al-Muttalib and not from Ali. Following this disappointment, the Shiʻat ʻAlī finally split from the majority Sunni Muslims and formed what are today the several Shiʻa denominations.

[edit] The Caliphate in Hispania

During the Ummayad dynasty, Hispania was an integral province of the Ummayad Caliphate ruled from Damascus, Syria. When the Caliphate was seized by the Abbasids, Al-Andalus (the Arab name for Hispania) split from the Abbasid Caliph in Baghdad to form their own caliphate. The Caliphate of Córdoba (خليفة قرطبة) ruled most of the Iberian Peninsula from the city of Córdoba from 929 to 1031. This period was characterized by remarkable flourishing in technology, trade and culture; many of the masterpieces of Spain were constructed in this period, including the famous Great Mosque of Córdoba. The title Caliph (خليفة) was claimed by Abd-ar-Rahman III on 16 January 929; he was previously known as the Emir of Córdoba (أمير قرطبة).

All Caliphs of Córdoba were members of the Umayyad dynasty; the same dynasty had held the title Emir of Córdoba and ruled over roughly the same territory since 756. The rule of the Caliphate is considered as the heyday of Muslim presence in the Iberian peninsula, before it fragmented into various taifas in the 11th century.

[edit] Abbasids, 8th–13th centuries

The Umayyad dynasty was overthrown by another family of Meccan origin, the Abbasids, in 750. The Abbasids had an unbroken line of Caliphs for over three centuries, consolidating Islamic rule and cultivating great intellectual and cultural developments in the Middle East. By 940, however, the power of the Caliphate under the Abbasids was waning as non-Arabs, particularly the Berbers of the Maghreb, the Turks, and later, in the latter half of the 13th century, the Mamluks in Egypt, gained influence, and the various subordinate sultans and emirs became increasingly independent.

However, the Caliphate endured as a symbolic position. During the period of the Abbasid dynasty, Abbasid claims to the caliphate did not go unchallenged. The Shiʻa Ubayd Allah al-Mahdi Billah of the Fatimid dynasty, which claimed descent from Muhammad through his daughter, claimed the title of Caliph in 909, creating a separate line of caliphs in North Africa.

Initially controlling Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia and Libya, the Fatimid caliphs extended their rule for the next 150 years, taking Egypt and Palestine, before the Abbasid dynasty was able to turn the tide, limiting Fatimid rule to Egypt. The Fatimid dynasty finally ended in 1171. The Umayyad dynasty, which had survived and come to rule over the Muslim provinces of Spain, reclaimed the title of Caliph in 929, lasting until it was overthrown in 1031.

[edit] Fatimids, 10th–12th centuries

Map of the Fatimid Caliphate also showing cities

The Fatimid Caliphate or al-Fātimiyyūn (Arabic الفاطميون) was a Shi'a dynasty that ruled over varying areas of the Maghreb, Egypt, Sicily, Malta and the Levant from 5 January 909 to 1171. The caliphate was ruled by the Fatimids, who established the Egyptian city of Cairo as their capital. The term Fatimite is sometimes used to refer to the citizens of this caliphate[citation needed]. The ruling elite of the state belonged to the Ismaili branch of Shi'ism. The leaders of the dynasty were also Shia Ismaili Imams, hence, they had a religious significance to Ismaili Muslims.

[edit] Shadow Caliphate, 13th–16th centuries

1258 saw the conquest of Baghdad and the execution of Abbasid caliph al-Musta'sim by Mongol forces under Hulagu Khan. A surviving member of the Abbasid house was installed as caliph at Cairo under the patronage of the newly formed Mamluk Sultanate three years later; however, this line of caliphs had generally little authority although some Abbasid rulers had the actual rule over the Mamluk Sultans. Later Muslim historians referred to it as a "shadow" caliphate. Thus, the title continued into the early 16th century.

[edit] Ottomans, 16th–20th century

Ottoman postage stamps issued for the Liannos City Post of Constantinople in 1865

Ottoman rulers (generally known as Sultans in the West) were known primarily by the title of Padishah and used the title of Caliph only sporadically. Mehmed II and his grandson Selim I used it to justify their conquest of Islamic countries. As the Ottoman Empire grew in size and strength, Ottoman rulers beginning with Selim I began to claim Caliphal authority.

Ottoman rulers used the title "Caliph" symbolically on many occasions but it was strengthened when the Ottoman Empire defeated the Mamluk Sultanate in 1517 and took control of most Arab lands. The last Abbasid Caliph at Cairo, al-Mutawakkil III, was taken into custody and was transported to Constantinople, where he reportedly surrendered the Caliphate to Selim I. According to Barthold, the first time the title of "Caliph" was used as a political instead of symbolic religious title by the Ottomans was the peace treaty with Russia in 1774.

The outcome of Russo-Turkish War of 1768-1774 war was disastrous for the Ottomans. Large territories, including those with large Muslim populations, such as Crimea, were lost to the Russian Empire. However, the Ottomans under Abdul Hamid I claimed a diplomatic victory by being allowed to remain the religious leader of Muslims in the now-independent Crimea as part of the peace treaty: in return Russia became the official protector of Christians in Ottoman territory. This was the first time the Ottoman caliph was acknowledged as having significance outside of Ottoman borders by a European power.

Around 1880 Sultan Abdul Hamid II reasserted the title as a way of countering Russian expansion into Muslim lands. His claim was most fervently accepted by the Muslims of British India. By the eve of the First World War, the Ottoman state, despite its weakness relative to Europe, represented the largest and most powerful independent Islamic political entity. The sultan also enjoyed some authority beyond the borders of his shrinking empire as caliph of Muslims in Egypt, India and Central Asia.

[edit] Sokoto, 19th century

The Sokoto Caliphate was an Islamic spiritual community in Nigeria, led by the Sultan of Sokoto, Sa’adu Abubakar. Founded during the Fulani Jihad in the early 19th century, it was one of the most powerful empires in sub-Saharan Africa prior to European conquest and colonization. The caliphate remained extant through the colonial period and afterwards, though with reduced power.

[edit] Khilafat Movement, 1920

In the 1920s, the Khilafat Movement, a movement to defend the Ottoman Caliphate, spread throughout the British colonial territories in what is now Pakistan. It was particularly strong in British India, where it formed a rallying point for some Indian Muslims as one of many anti-British Indian political movements. Its leaders included Maulana Mohammad Ali, his brother Shawkat Ali, and Abul Kalam Azad, Mukhtar Ahmed Ansari, and Barrister Muhammad Jan Abbasi. For a time it worked in alliance with Hindu communities and was supported by Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, who was a member of the Central Khilafat Committee.[7][8] However, the movement lost its momentum after the arrest or flight of its leaders, and a series of offshoots splintered off from the main organization. However by 1921, the movement being essentially religious in nature, culminated into genocide of non-muslim communities in Malabar. Further, the newly established nation states in the Arabian peninsula, where Islam originated, were themselves opposed to the re-establishment of the Caliphate due to their own socio-political reasons.

[edit] End of the Caliphate, 1924

On March 3, 1924, the first President of the Turkish Republic, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, as part of his reforms, constitutionally abolished the institution of the Caliphate. Its powers within Turkey were transferred to the Grand National Assembly of Turkey, the parliament of the newly formed Turkish Republic. The title was then claimed by King Hussein bin Ali of Hejaz, leader of the Arab Revolt, but his kingdom was defeated and annexed by Ibn Saud in 1925. The title has since been inactive.

A summit was convened at Cairo in 1926 to discuss the revival of the Caliphate, but most Muslim countries did not participate and no action was taken to implement the summit's resolutions.

Though the title Ameer al-Mumineen was adopted by the King of Morocco and by Mullah Mohammed Omar, former head of the now-defunct Taliban regime of Afghanistan, neither claimed any legal standing or authority over Muslims outside the borders of their respective countries.

[edit] Religious basis

[edit] Qur'an

The following excerpt from the Qur'an, known as the 'Istikhlaf Verse', is used by some to argue for a Quranic basis for Caliphate:

God has promised those of you who have attained to faith and do righteous deeds that, of a certainty, He will make them Khulifa on earth, even as He caused [some of] those who lived before them to become Khulifa; and that, of a certainty, He will firmly establish for them the religion which He has been pleased to bestow on them; and that, of a certainty, He will cause their erstwhile state of fear to be replaced by a sense of security [seeing that] they worship Me [alone], not ascribing divine powers to aught beside Me. But all who, after [having understood] this, choose to deny the truth – it is they, they who are truly iniquitous!" [24:55] (Surah Al-Nur, Verse 55)

In the above verse the word Khulifa (the plural of Khalifa) has been variously translated as "successors" and "ones who accede to power".

Small subsections of Sunni Islamism argue that to govern a state by Islamic law (Shariah) is, by definition, to rule via the Caliphate, and use the following verses to sustain their claim.

So govern between the people by that which God has revealed (Islam), and follow not their vain desires, beware of them in case they seduce you from just some part of that which God has revealed to you

O you who believe! Obey God, and obey the messenger and then those among you who are in authority; and if you have a dispute concerning any matter, refer it to God and the messenger's rulings, if you are (in truth) believers in God and the Last Day. That is better and more seemly in the end.