Houston residents evacuate their homes amid Harvey flooding after a reservoir spilled over for the first time in history. (Dalton Bennett, Whitney Shefte/The Washington Post)

HOUSTON — The biggest rainstorm in the history of the continental United States finally began to move away from Houston on Tuesday, as the remnants of Hurricane Harvey and its endless, merciless rain bands spun east to menace Louisiana instead.

A storm surge warning for the coast from Holly Beach to Morgan City, La., said water levels could rise two to four feet above normally dry land when the center of the storm approached for a second landfall Tuesday night, The Washington Post’s Capital Weather Gang reported. To the east, New Orleans was under a flash flood warning Tuesday morning.

Louisiana Gov. John Bel Edwards (D) said in a news conference Tuesday to “prepare and pray.”

In Texas, the storm was still moving east, still deadly

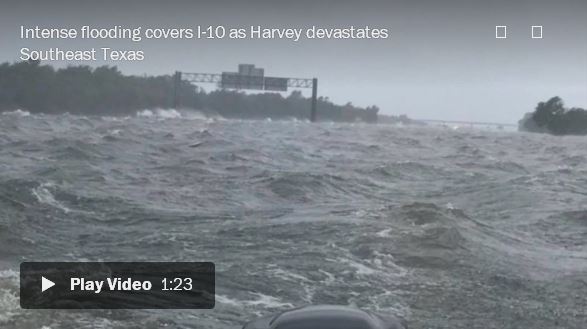

Waves were seen lapping overs I-10 near Winnie, Tex., on Aug. 29 as floodwater continued to rise. (Logan Wheat)

In Beaumont, Tex., 85 miles east of Houston, at least 10 inches of rain fell on Tuesday afternoon alone. In the deluge, a mother and child got out of their car on a flooded freeway service road and were swept away. The child clung to her mother for half a mile. Police and firefighters got to them just before they went under a trestle and were lost for good. Only the child survived, police said.

The National Weather Service issued a flash flood emergency — its most severe flood alert — into Tuesday night.

After more than 50 inches of rain over four days, Houston was less of a city and more of an archipelago: a chain of urbanized islands in a muddy brown sea. All around it, flat-bottomed boats and helicopters were still plucking victims from rooftops, and water was still pouring in from overfilled reservoirs and swollen rivers.

Between 25 and 30 percent of Harris County — home to 4.5 million people in Houston and its near suburbs — was flooded by Tuesday afternoon, according to an estimate from Jeff Lindner, a meteorologist with the county flood control district. That’s at least 444 square miles, an area six times the size of the District of Columbia.

Across Houston on Tuesday, there were some new reasons for hope: The rain turned from sheets into mere drops. Fast-food outlets reopened. When a downtown convention center became a shelter for the displaced, volunteers lined up around the block to help.

But there was a realization that the storm’s most awful damage was still unknown — scattered out in those disconnected islands, or hidden under the water.

Mayor Sylvester Turner (D) imposed a curfew starting Tuesday from midnight to 5 a.m. Central Time to deter looting of abandoned homes.

“There are some who might want to take advantage of this situation, so even before it gets a foothold in the city, we just need to hold things in check,” Turner said at a news conference.

Authorities added that there had been reports of people impersonating law enforcement officers in communities such as Kingwood, falsely telling people they needed to evacuate.

On Tuesday morning authorities discovered the body of a Houston police officer who had drowned in his patrol car two days earlier, at the storm’s height. Sgt. Steve Perez, a veteran officer, was on his way to work Sunday morning — spending 2 ½ hours looking for a path through rain-lashed streets — when he drove into a flooded underpass.

Houston Police Chief Art Acevedo said that Perez’s wife had asked him not to go in that day. He went, Acevedo said, “because he has that in his DNA.”

In all, authorities said at least 22 people had been confirmed dead from the storm. But they said it was difficult to know how many more were missing. They also said it is too early to assess the total number of homes and other buildings damaged, in part because rescue crews were still having trouble even reaching some areas because of flooded or flood-damaged roads, said Francisco Sanchez, spokesman for the Harris County Office of Homeland Security and Emergency Management.

“We’re still in the middle of the response,” he said.

Authorities said more than 13,000 people had been rescued from floodwaters, according to the Associated Press, but that number was surely low. Many had been rescued by strangers with boats, who had rescued so many that they themselves had lost count. They left behind homes that could be flooded for days, or weeks, and perhaps lost forever.

Officials said more than 13,300 people were already in shelters. Federal authorities estimated that 30,000 people could be forced from their homes in Texas and surrounding states.

All around Houston on Tuesday, the helping and the helpless repeated the same thing.

This doesn’t happen here.

“I’ve lived here since 1994, and it’s never been this high,” said Bonnie McKenna, a retired flight attendant living in Kingwood, along the raging San Jacinto River on Houston’s northeast side.

McKenna’s house was dry, but down the street rescue boats were unloading neighbors rescued from flooded streets nearby. McKenna didn’t have a boat.

But she did have a blanket.

She cut it into quarters and offered the pieces to soggy evacuees when they got off on dry land.

“I’m thankful it didn’t come to my house, but I’m very sad for the people who have just lost everything,” McKenna said.

About 30 miles north of the city, some people weren’t as fortunate as McKenna but they made do.

At no point was Carol Headrick scared, she said.

Not when they ordered evacuations. Not when Lake Houston’s waters rose to the height of the front desk lobby at her Kingwood nursing home. Not when rescue crews told her she had to leave. And definitely not when they took her on a pontoon boat ride.

“I never was scared,” Headrick said as her face, shocked by a reporter’s question morphed from one of feigned outrage to a mischievous smile. It was as though she were about to reveal some delicious secret. “I’ve got my Bible. And God promised he never was going to do this again.”

The 83-year-old woman’s lively disposition betrayed no hidden fear amid the immense loss and devastation of historic flooding in Houston brought on by Harvey this week.

No, Headrick was too busy deciphering the crackle of her old handheld AM-FM radio to be bothered with worry. She had to keep her nursing home mates informed. They sat in a U-shaped group in the center of Kingwood Bible Church’s multipurpose room chit-chatting about the Louisiana State University tigers (Headrick’s favorite team), making the most of their unusual circumstances and choosing which quilt-draped air mattress they would sleep on that night.

The residents of Arbor Terrace, a senior living facility in the now-underwater Kingwood Town Center, had little time to grab anything. Lupe Herasimchuk didn’t have time to retrieve her CPAP machine, a device that helps those with sleep apnea breathe easier. And they came only with the clothes they had on when emergency personnel arrived at the waterlogged facility.

“It happened so fast,” Herasimchuk said. “I mean, I didn’t bring anything.”

But the Kingwood community made sure Herasimchuk and her neighbors were not left wanting. Neighbors from across the 14,000-acre planned community brought bundles of donations — everything from toiletries to linens and clothes, lots of it. Volunteers at the church were busy sorting out the tall piles of stuff they had received.

Headrick, she said, is pretty low maintenance. Besides her holy book, she grabbed her medicine before being led out of her third-floor apartment to a waiting rescue. She had all she needed, that is, until she spotted a pink shirt with a gold design someone had donated among the goods.

She didn’t want to have to leave: “I felt like I was safe,” Headrick said. “I felt like there was no place they take us.”

But when she saw that the floodwaters had overwhelmed the first floor of the multilevel complex — as high as five feet — Headrick went along peaceably. And gratefully, she said. Headrick was happy with the sandwiches she was given, the care from volunteers and to still be among her friends.

“Last week they gave us these special glasses to watch the eclipse and who would have thought we’d be here now,” she said.

Headrick said she “lived through Alicia and all the others” referencing storms dating to 1983. “But nothing this bad before. God promised he’d never do this again.”

President Trump flew to Texas on Tuesday, and he visited both Corpus Christi — near where the storm made landfall — and state officials in Austin. At one point, he shouted a message to a crowd outside a fire station in Corpus Christi.

“This is historic, it’s epic what happened. But you know what, it happened in Texas and Texas can handle anything,” he told the crowd, which applauded his remarks and cheered more loudly when he waved the Texas state flag.

The Labor Department on Tuesday announced that it had approved an initial $10 million grant to help with cleanup efforts in Texas. Trump on Monday declared “emergency conditions” in Louisiana, where the storm was headed next.

Before Harvey struck this weekend, the biggest recorded rainstorm in the continental United States had been Tropical Storm Amelia, which dumped 48 inches on Texas in 1978 (even larger storms have been recorded in Hawaii).

President Trump visited Texas Aug. 29, after Hurricane Harvey struck parts of the state. Here’s how his predecessors handled natural disasters. (Victoria Walker/The Washington Post)

Harvey — which drifted out of the jet stream and spun around Houston like a top — smashed the record. By Tuesday afternoon, a rain gauge near Mont Belvieu, 40 miles east of Houston, had recorded 51.9 inches of rain.

Over Harris County alone, Lindner estimated that more than a trillion gallons of rain fell. That was like letting Niagara Falls run full blast onto Houston for 15 days straight.

The water rushed off the concrete of the expanding city and overwhelmed the meandering bayous that were its natural path to the sea. The hardest-hit areas were often in the south and southeast, the downstream end of the waterways.

But the water was everywhere. A map of flooded streets, compiled by the Houston Chronicle, showed a city dotted with blue. There were concentrations to the west of the city, too, where water had filled up two enormous upstream reservoirs, named Addicks and Barker, that were built to shield the city from floods like this.

Officials released water from those reservoirs to ease the pressure, but at least one of the reservoirs still overtopped its banks. More than 3,000 homes were flooded around the reservoirs.

They may remain flooded for some time. The Army Corps of Engineers said it would continue to release water from the reservoirs for weeks, to make room in case another rain comes.

“We’re still in tropical storm season,” said Edmond Russo, an official with the Corps of Engineers.

Across Texas, the storm has shut down 14 oil refineries, causing damage at some that released harmful chemicals.

In Crosby, Tex., a fertilizer plant was in critical condition Tuesday night after its refrigeration system and inundated backup power generators failed, raising the possibility that the volatile chemicals on the site would explode.

Arkema, a maker of organic peroxides, evacuated all the personnel from the plant and was attempting to operate the facility remotely. The material must be kept at low temperatures to avoid combustion.

Around the city, schools and universities were closed, with some unable to say when they would reopen.

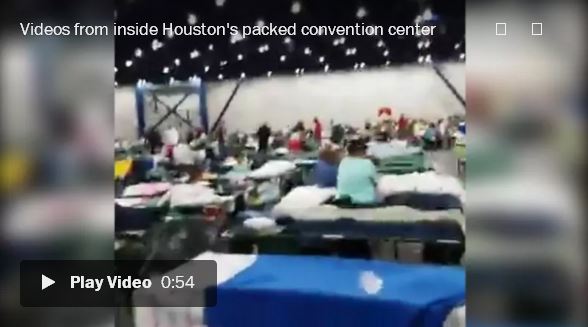

Some of the thousands of evacuees taking refuge in Houston's George R. Brown Convention Center shared videos of the shelter on social media amid Tropical Storm Harvey's record-level flooding. (The Washington Post)

The George R. Brown Convention Center downtown had taken in 10,000 people as of Tuesday morning, Turner said. That number is double the center’s anticipated capacity of 5,000. The city said it was opening two new shelters in the NRG Center, a convention center near the old Astrodome, and the Toyota Center, home of the NBA Houston Rockets.

The convention center is the landing site for all air evacuations, said Charles Maltbie, a regional disaster officer for the Red Cross, and bus evacuations are being diverted to other shelters. When asked what the center’s top capacity is, he said: “We will meet the need.”

About 250 miles to the north, the city of Dallas was preparing to take at least 6,000 evacuees from the Houston area, according to Dallas County Judge Clay Jenkins (D), the county’s top official. There were showers. Phone-charging stations. There was a dining hall manned by volunteers, including the Texas Baptist Men and local Israeli-American and Muslim-American groups.

The Dallas shelter was still mostly empty Tuesday because the storm was too bad to get evacuees out of Houston.

“The planes are grounded, so we can’t get C-130s in” with evacuees, Jenkins said. “The roads are covered with water, so we can’t get buses in.”

Dallas housed 28,000 evacuees after Hurricane Katrina in 2005, Jenkins said. He said he’s not sure if that many will come this time.

“We don’t know what we’ll get,” he said, “until the water recedes.”

Hundreds of families found shelter at Wedgewood Elementary School in Friendswood, Tex., after Tropical Storm Harvey's floodwaters forced them out of their homes. (Zoeann Murphy, Thomas Johnson/The Washington Post)

That was the future. In Houston on Tuesday, the city’s islands were still busy with the present.

Evacuees came by helicopter, by truck, by pool float. They were brought in by the National Guard, by the fire department, by volunteers from the “Cajun Navy,” and by a crew of brewery employees who had once bought a surplus military truck on a lark and now used it to rescue their neighbors.

As the rain began to subside, and some bayous began to recede, both those who were saved — and those who did the saving — began to reflect on what comes next.

One of them was Tom Cullen, 54, who had rushed over to save his parents Sunday, as their backyard filled with water. He drove his Ford pickup until the truck couldn’t go farther, hitting hip-deep water.

Cullen eventually sat down and cried.Then he took a one-seat kayak he’d borrowed from a neighbor. He got both his parents — ages 81 and 88 — into the kayak, then into the truck, and then safely home.

“When I think of what could have happened, reality just hit me right there,” he said, his voice breaking. “With all they have done for me since I was born, there was no way I wasn’t going over there. Anyone would do the same for their parents.”

The home his parents left behind is filled with more than four feet of water. It is still rising, he said.

Fahrenthold reported from Washington. Emily Wax-Thibodeaux, Alex Horton, Dylan Baddour and Brittney Martin in Houston; Mark Berman, Steven Mufson, Ed O’Keefe, Wesley Lowery, Thomas Gibbons-Neff, Katie Zezima, and Jason Samenow in Washington; Ashley Cusick in New Orleans and Leslie Fain in Lake Charles, La.; and Mary Lee Grant in Corpus Christi, Tex., contributed to this report.