Image copyrightSPL

Image copyrightSPLUK scientists have been given the go-ahead by the fertility regulator to genetically modify human embryos.

The research will take place at the Francis Crick Institute in London and aims to provide a deeper understanding of the earliest moments of human life.

The experiments will take place in the first seven days after fertilisation and could explain what goes wrong in miscarriage.

It will be illegal for the scientists to implant the embryos into a woman.

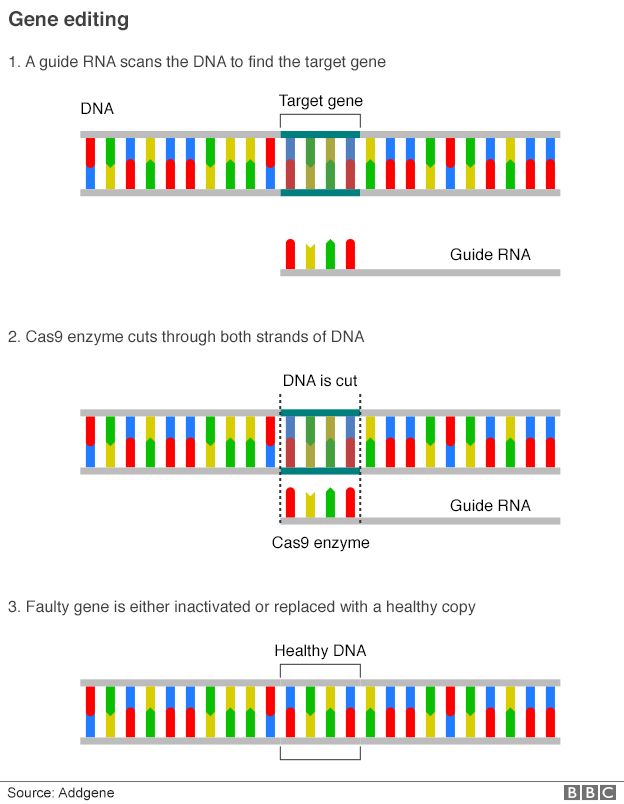

Gene editing is the manipulation of our DNA - the blueprint of life.

In a world-first last year, scientists in China announced that they had carried out gene editing in human embryos to correct a gene that causes a blood disorder.

The field is attracting controversy, with some saying that altering the DNA of an embryo is a step too far and opens the door to designer babies.

Infertility

Earlier this year scientist Dr Kathy Niakan explained why she had applied to edit human embryos: "We would really like to understand the genes needed for a human embryo to develop successfully into a healthy baby.

"The reason why it is so important is because miscarriages and infertility are extremely common, but they're not very well understood."

Out of every 100 fertilised eggs, fewer than 50 reach the early blastocyst stage, 25 implant into the womb and only 13 develop beyond three months.

The regulator, the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA), has given its approval and the experiments could start in the next few months.

Paul Nurse, the director of the Crick, said: "I am delighted that the HFEA has approved Dr Niakan's application.

"Dr Niakan's proposed research is important for understanding how a healthy human embryo develops and will enhance our understanding of IVF success rates, by looking at the very earliest stage of human development."

Dr Niakan, who has spent a decade researching human development, is trying to understand the first seven days.

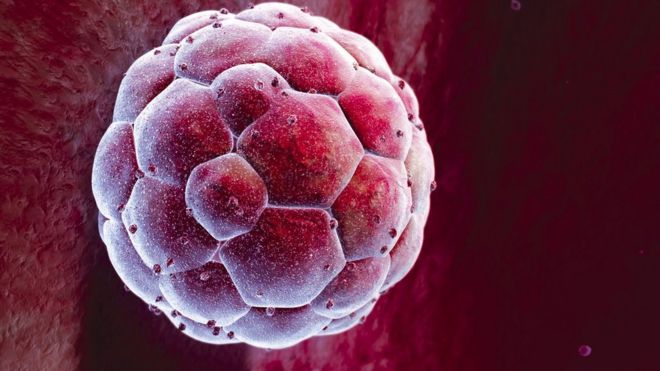

During this time we go from a fertilised egg to a structure called a blastocyst, containing 200-300 cells.

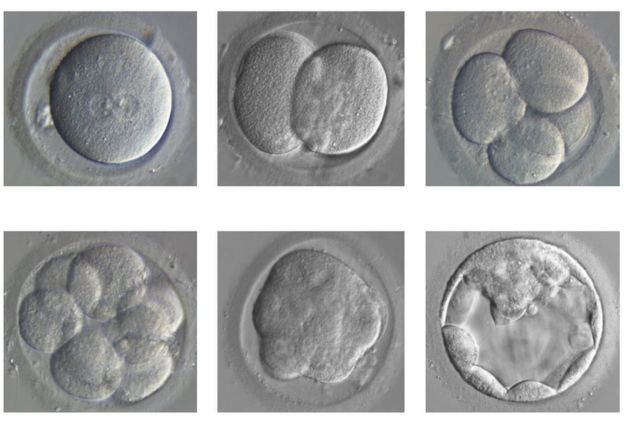

Image copyrightKathy NiakanImage captionThe embryo divides and develops from a single fertilised egg (top left) to a blastocyst (bottom right)

Image copyrightKathy NiakanImage captionThe embryo divides and develops from a single fertilised egg (top left) to a blastocyst (bottom right)But even at this early blastocyst stage, some cells have been organised to perform specific roles - some go on to form the placenta, others the yolk sac and others ultimately us.

During this period, parts of our DNA are highly active.

It is likely these genes are guiding our early development, but it is unclear exactly what they are doing or what goes wrong in miscarriage.

Dr Sarah Chan, from the University of Edinburgh, said: "The use of genome editing technologies in embryo research touches on some sensitive issues, therefore it is appropriate that this research and its ethical implications have been carefully considered by the HFEA before being given approval to proceed.

"We should feel confident that our regulatory system in this area is functioning well to keep science aligned with social interests."